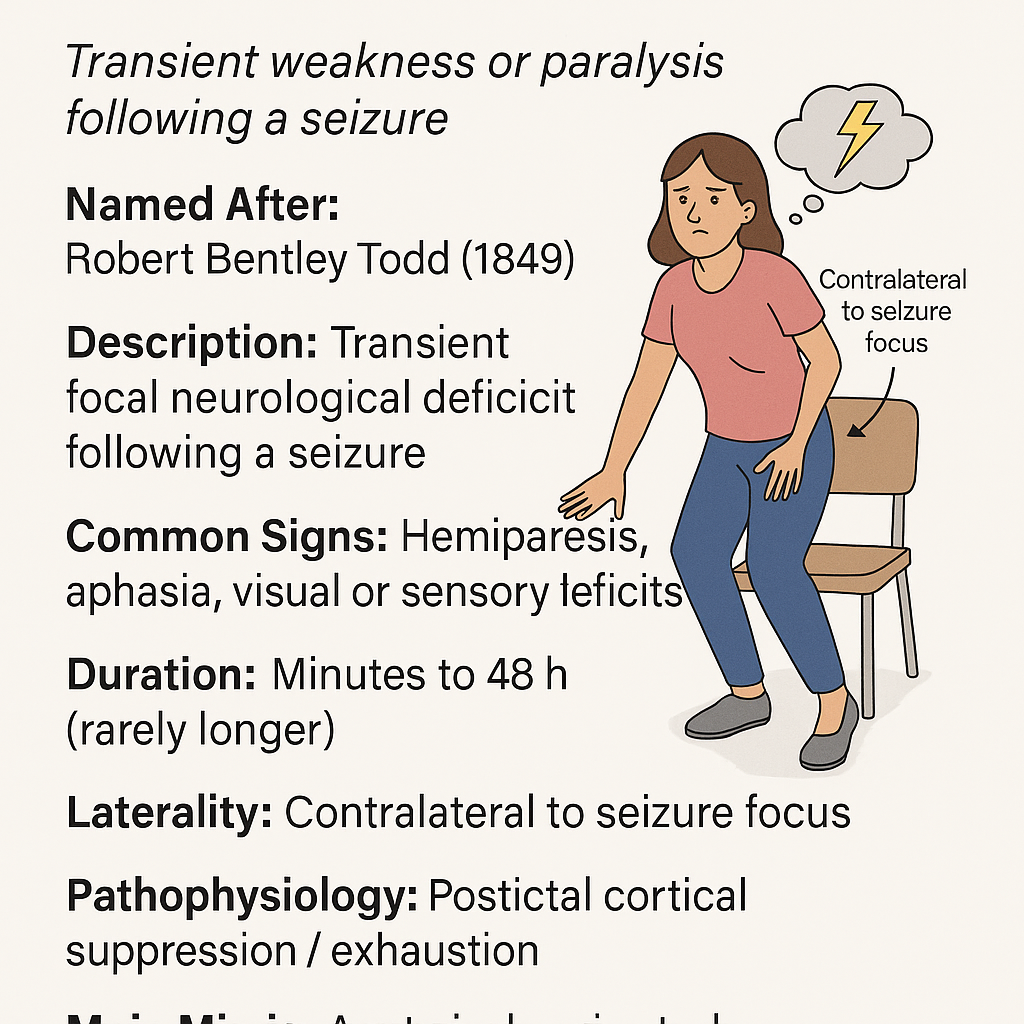

Todd’s Palsy: Transient Weakness Following a Seizure

Todd’s palsy—also known as postictal paralysis or postictal paresis—is a temporary neurological deficit that occurs after a focal seizure, usually involving motor symptoms. This phenomenon is crucial to recognize clinically, as it can resemble a stroke and provides valuable information about the seizure’s origin in the brain.

1. Historical Background and Eponym

Robert Bentley Todd (1809–1860) was a pioneering Irish physician, physiologist, and neurologist who made significant contributions across medicine. Educated in Dublin, Oxford, and London, he became a professor of physiology at King’s College London and played a central role in establishing King’s College Hospital and advancing nursing education.

In 1849, during his Lumleian Lectures, Todd described cases of what he termed “epileptic hemiplegia”—a unilateral paralysis that follows a seizure. He presented detailed cases, noting that the paralysis usually resolved within hours or days. Although earlier reports existed, Todd’s work remains the first detailed clinical account, and the term “Todd’s paralysis” is now firmly associated with his name .

Todd was also notable for being a pioneer in:

Developing an electrical theory of epilepsy

Introducing the anatomical concepts of afferent and efferent nerves

Laying the foundation for modern understanding of post-seizure paralysis

2. Clinical Definition and Features

Todd’s palsy manifests as:

Focal motor weakness or paralysis, typically involving limb(s)

Occasionally aphasia, visual field deficits, or sensory loss, depending on seizure localization

Happens immediately after the seizure

Reversible within a few minutes to up to 48 hours (rarely longer)

This postictal deficit is always contralateral to the brain area where the seizure occurred.

3. Pathophysiology

While the exact mechanism isn't fully settled, current theories include:

Neuronal exhaustion in the postictal cortex

Enhanced inhibitory postictal activity

Local metabolic dysfunction, such as cortical hypoperfusion or ion channel changes

Imaging studies during Todd’s palsy often reveal regional hypoperfusion in the affected cortex, distinguishing it from active seizure zones, which show hyperperfusion .

4. Differential Diagnosis

Because Todd’s palsy can mimic stroke, it’s vital to differentiate it from other acute neurological conditions:

5. Diagnosis

Diagnosing Todd’s palsy is primarily clinical:

Key steps:

Confirm seizure history (witnessed event, focal movements)

Perform a neurological exam showing focal weakness with preserved reflexes

Use neuroimaging (CT/MRI) to rule out stroke or structural lesions

EEG may show slowing in the affected area during the postictal phase

Imaging is crucial in emergency settings to exclude life-threatening mimics like stroke.

6. Management and Prognosis

There’s no direct treatment for Todd’s palsy itself; the focus is on:

Seizure management, through initiation or adjustment of antiepileptic medications

Avoiding stroke misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatments (e.g., unnecessary thrombolysis)

Patient education and reassurance — symptoms typically resolve completely

Prognosis is excellent; most patients recover fully within minutes to 48 hours .

Recurrent Todd’s palsy may occur with recurrent seizures.

7. Summary Table: Todd’s Palsy Overview

8. Conclusion

Todd’s palsy is an important neurological sign that reminds clinicians to distinguish post-seizure weakness from acute stroke. Robert Bentley Todd’s detailed clinical descriptions laid the groundwork for understanding this phenomenon, emphasizing both neurological localization and cautious interpretation. Recognizing this transient palsy today helps ensure patients receive appropriate care—note by distinguishing a benign condition from a medical emergency, not by dismissing it.

Comment