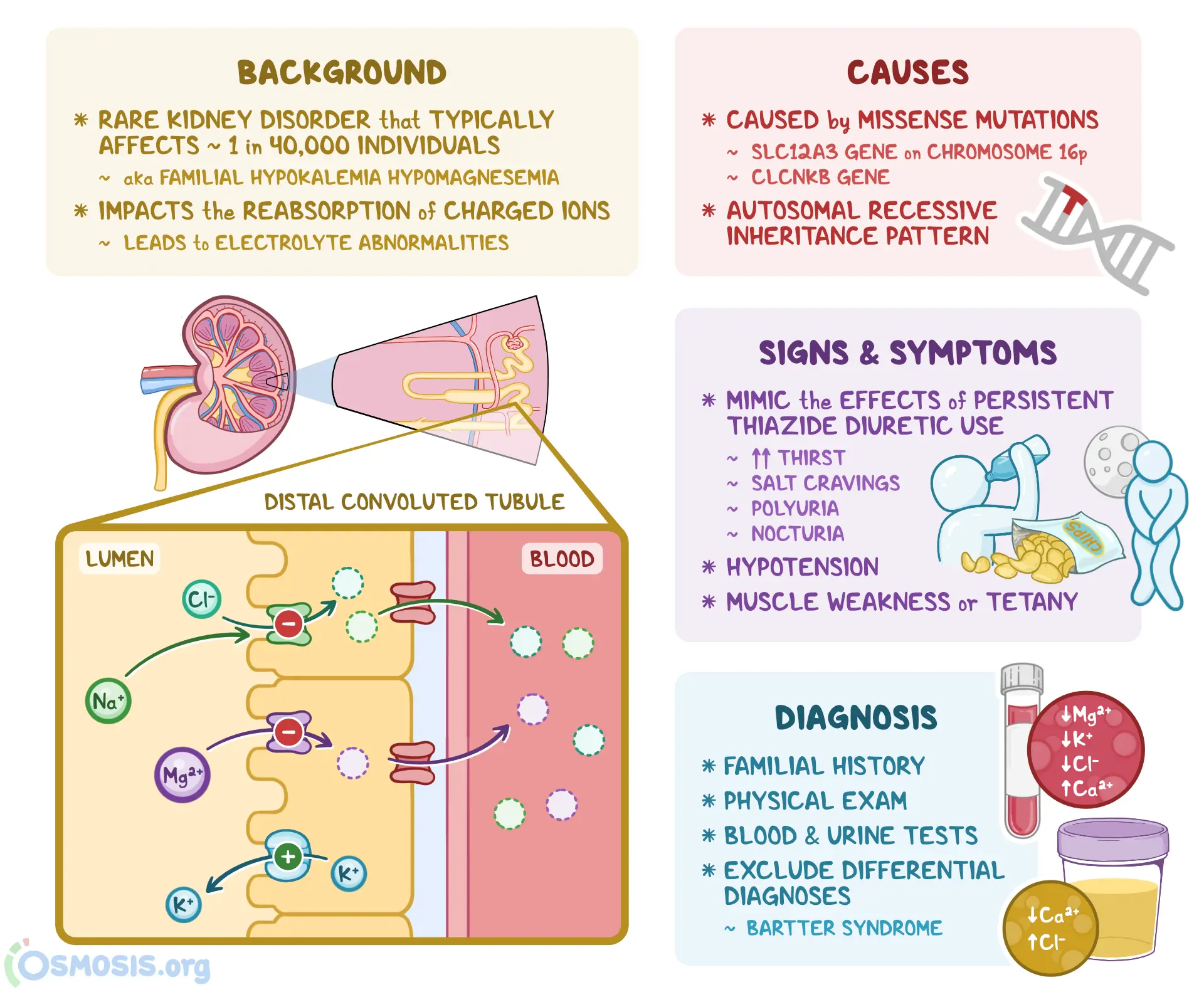

Gitelman syndrome (GS) is a rare inherited kidney disorder characterized by defective salt reabsorption in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT). It leads to low potassium (hypokalemia), low magnesium (hypomagnesemia), low urinary calcium (hypocalciuria), and metabolic alkalosis. Often described as the “milder cousin” of Bartter syndrome, Gitelman syndrome involves a specific transporter defect and has a distinct clinical profile.

1. Historical Background and Eponym

The syndrome was first described in 1966 by American nephrologist Dr. Hillel J. Gitelman. He identified adult patients with hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia in the absence of hypertension and without typical Bartter features. Later genetic studies confirmed that the condition is distinct and is caused by mutations in the SLC12A3 gene encoding the thiazide-sensitive Na⁺–Cl⁻ cotransporter (NCC).

2. Genetic and Pathophysiological Basis

Inheritance: Autosomal recessive

Gene involved: SLC12A3 (primarily), occasionally CLCNKB and other rare variants

Protein affected: Thiazide-sensitive Na⁺–Cl⁻ cotransporter (NCC) in the DCT

Pathophysiology: Impaired NaCl reabsorption in DCT → salt wasting, mild volume depletion → activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) → increased K⁺ and H⁺ loss → hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis. Also, there is impaired magnesium reabsorption (mechanism partly via TRPM6 channel down-regulation) → hypomagnesemia. Urinary calcium is low because DCT reabsorption of calcium is enhanced when sodium delivery is reduced.

3. Clinical Presentation

Symptoms often appear in late childhood or adulthood, and the presentation is generally milder compared to Bartter syndrome.

Typical features include:

Muscle cramps, weakness, fatigue (due to hypokalemia/hypomagnesemia)

Salt craving, increased thirst, nocturia or polyuria (due to salt wasting)

Cardiac arrhythmias or palpitations (in severe electrolyte disturbance)

Normal or low blood pressure (due to chronic salt loss)

Some patients may even be asymptomatic and are found incidentally on blood tests.

4. Key Laboratory Findings

Serum potassium (K⁺): Low

Serum magnesium (Mg²⁺): Low

Urinary calcium: Low (hypocalciuria)

Blood pH / bicarbonate: Elevated (metabolic alkalosis)

Plasma renin & aldosterone: Elevated (secondary hyperaldosteronism)

Blood pressure: Typically normal or low

These findings help distinguish GS from other causes of hypokalemia.

5. Differential Diagnosis

Bartter syndrome: Onset earlier (often childhood), hypercalciuria (rather than low), usually no hypomagnesemia

Diuretic abuse (especially thiazides): Similar lab pattern; drug screen may help

Liddle syndrome: Hypertension with hypokalemia and low renin/aldosterone

Chronic vomiting or laxative abuse: Hypokalemia and alkalosis but other features differ

Accurate diagnosis avoids mismanagement.

6. Diagnosis

Clinical suspicion arises when the lab pattern of hypokalemia + hypomagnesemia + hypocalciuria + metabolic alkalosis is seen. Confirmatory tests include:

Genetic testing for SLC12A3 mutations

Exclude secondary causes (diuretics, vomiting)

In most cases, renal imaging is not required as structure is normal

7. Management

Although there is no cure, management aims to control symptoms and prevent complications:

Potassium supplementation (oral, sometimes high doses)

Magnesium supplementation (often necessary)

Potassium‐sparing agents (e.g., amiloride, spironolactone) may reduce K⁺ loss

Liberal salt intake

Avoid medications that exacerbate electrolyte loss (e.g., thiazide/loop diuretics)

Monitor cardiac rhythm and muscle symptoms

With proper management, patients generally do well.

8. Prognosis

Prognosis is generally excellent; life expectancy is unaffected. Many patients lead normal lives, although persistent fatigue, cramps, and periodic symptomatic electrolyte derangements may affect quality of life. Lifelong monitoring is recommended.

9. Summary Table: Gitelman Syndrome Overview

10. Conclusion

Gitelman syndrome is a distinctive renal tubular disorder that presents with a tell-tale biochemical signature. Recognizing the combination of hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypocalciuria and alkalosis—and linking it to the underlying transporter defect—is key. With appropriate treatment and follow-up, patients can maintain good quality of life. The syndrome also illustrates how a single gene defect can lead to complex electrolyte and renal consequences.

Comment